The Gloucester Candlestick has been faithfully recreated in a new 3D print.

While today’s candlesticks are often slim, sleek affairs, the same could not be said of medieval cathedral decorations. Created in the 12th century, the original Gloucester Candlestick was crafted to meet the then-in-demand intricate, Romanesque aesthetic. Designed for, naturally, the Gloucester Cathedral, the candlestick did not stay there very long at all. Much of its history is rather a question mark, but some nine centuries after its commission, the piece will be returning to its roots in detailed, accurate replicate.

Making The Gloucester Candlestick

A candlestick may not seem the most exciting of builds, but this serves as a stunning example of art and aesthetic — and survival.

The original candlestick traces its origins to 1104-1113, when the Church of St Peter in Gloucester, later renamed Gloucester Cathedral, was run by Abbot Peter. Abbot Peter was continuing the work of the previous abbot, Serlo, who sought to expand the church. The Benedictine community of the time had the wealth and status to lead to the making of such an intricate showpiece. The piece was likely made in around 1110, and inscribed:

“The devotion of Abbot Peter and his gentle flock gave me to the Church of St Peter of Gloucester.”

To make the candlestick, artisans of the time turned to the ever-popular lost wax casting technique.

It was cast in three parts: the base, the stem, and the drip pan. Each section was modelled in wax, creating intricate designs that many have referenced as the struggle of vice and virtue. Detailed dragons, humans, angels, and everything in between are entangled throughout the candlestick, each originally formed in the wax.

“Wax sprues, known as runners and risers, were attached to the models in strategic places. These created channels to enable the flow of the metal to the mould and the escape of gases during casting,” the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) explains of its manufacture.

The final piece was made of a copper alloy, gilded to perfection. Reflecting both the job of a candlestick and the themes of its design work, an inscription on the outside of the drip pan reads:

“Burden of light, work of virtue, brilliantly shining teaching preaches so that Man may not be darkened by sin.”

A likely early — still medieval — repair job also saw the insertion of two pieces of gilded copper tubing to hold the candlestick together. The V&A performed Energy Dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) to examine the work, finding that the tubing’s elements “are comparable to those in other medieval examples,” leading them to understand that the tubing may have been put in centuries ago to steady the ornate structure. In doing so, it changed the look from an openwork creation to more of a raised relief, but held it together when moving or disassembly and reassembly may have otherwise led to its collapse. The V&A has since removed the tubing, showing again the openwork structuring of hte original design.

The Journey Of The Gloucester Candlestick

Following initial its 1110-ish display in the church, the candlestick went on quite a journey over the next decades and centuries.

Much of its trail is left a sort of mystery to history — but what is notable is that the piece survived all that time. Especially as the aesthetic changed, such as from Romanesque to Gothic, often such pieces of metalwork were melted down and reused in new pieces to celebrate new techniques and preferences.

St. Peter’s Abbey caught fire in 1122. Nearly everything was destroyed. The candlestick was not accounted for in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s account of the very few surviving articles, and all that is known is that it was not there after the fire. It could have been looted, or already rehomed at the time.

The next known location of the candlestick was when it popped up in France, at Le Mans Cathedral. Another inscription, on the inside of the drip pan, reads:

“Thomas Pociencis gave this to the Church of Le Mans when the sun renewed the year.”

Dear Thomas of Poché did not note which year was renewed, so historians have been left guessing. Among the events noted as potentially impacting the trail of candlestick are St Peter’s Abbey being subjected to Welsh raids and the selling of valuables for taxes, though the candlestick may not have already found its way to France before these events.

Following its stay at Le Mans Cathedral, a Parisian collector sold the Gloucester Candlestick to the V&A in 1861.

Remaking The Gloucester Candlestick

The V&A has been caring for the candlestick these last 159 years, displaying it as Museum no. 7649-1861. It was here that the copper tubing was discovered as new technologies made more possible to understand such holdings.

And it is here that the candlestick is now better understood and can now be better shown — including in its original home in Gloucester.

The V&A and Gloucester Cathedral have worked with Gloucester-based Renishaw and a foundry in Stroud to create two new replicas of the medieval piece. The candlestick is now the V&A collections’ earliest piece to receive such treatment.

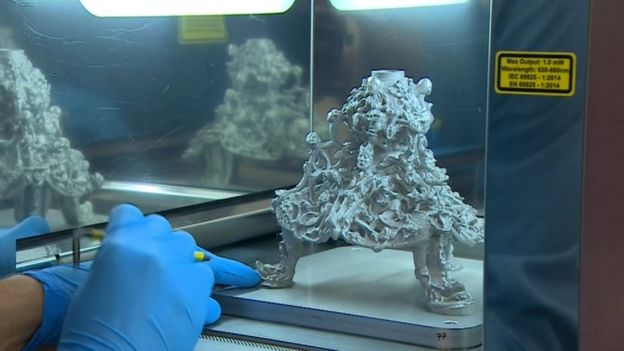

Renishaw engineers 3D scanned the candlestick in detail, mapping it point by point — using what looks like an Artec Eva 3D scanner — to develop a model.

They then 3D printed two replicas in aluminum. The BBC’s coverage didn’t go into much detail here, save to note that the prints took place “over several days,” then undergoing hand-finishing for the detail work and the Stroud foundry applying a gold patina to match the original look.

“I can see this technology being used a lot more for this type of work – replicating parts that are valuable and that you can let people touch,” said Renishaw’s Paul Govan, who called working on this project “a privilege.”

The replicas are set to be installed at the cathedral ahead of early September’s Gloucester History Festival. The Festival will also feature the pieces heavily in activities and lectures, complete with online content. Following the Festival, one candlestick will be located in the Cathedral’s Tribune Gallery, and another in the Treasury.

“It’s been so long away from us, and been through such trials whilst it’s been away as well,” said Gloucester Cathedral archivist Rebecca Phillips. “Who knows what it went through during the French revolution?

“It’s lovely to have it back, and also it’s now accessible to anyone of faith and no faith as well. The beauty of it is just gorgeous.”

Gloucester Cathedral is finalizing its preparation, and is currently seeking to raise £14,000 to cover, they explain, the costs of:

- Patination for both replicas to match the original

- Installation, lighting and a secure enclosure for replica in the Tribune Chapel

- Interpretation for visitors telling the story of the candlestick and the making of the replicas

Such historical recreations are, as Renishaw’s Govan pointed out, increasing both in activity and simply increasing access to hands-on history.

That 3D printing is able to faithfully recreate Romanesque metalworking is a strong testament to the accuracy and reliability of the technology — and certainly a nice way to return artifacts to their original homes.

That the V&A has been encouraging high-tech recreations of its collections is heartening, as is the historical Gloucester Cathedral’s commitment itself to advanced technologies; while writing this piece, I also enjoyed the opportunity for a 360-degree digital tour of the Cathedral.

Via BBC, Gloucester Cathedral, and Victoria and Albert Museum