![Andretti racing [Image via Stratasys]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Andretti2_img_5eb09c7a3c63d.jpg)

Mac and cheese. Lucy and Ethel. Penn and Teller. Racing and 3D printing. Sometimes it’s just a good pairing.

They go together, as it turns out, like rama lama lama ka dinga da dinga dong. But, gratuitous Grease references aside, why?

Similarly to what we’re seeing in aerospace, there’s something of a trickle-down effect as 3D printing industrializes and becomes more reliable. Additive manufacturing is being qualified for use in demanding environments, like rocket engines, where regulations are especially (and for good reason) strict. Once the tech can prove repeatable, high-quality results that can be qualified for use, less demanding applications can easily fall in line. The big guys have done the most strenuous work for them, in a way, and laid that foundation.

The automotive industry is a major market for 3D printing, and has been for decades. Most applications though are in prototyping, tooling, jigs, and fixtures, with spare parts on the rise as well. Only more recently have we really been seeing end-use parts becoming more mainstream in the automotive market, and these a few at a time.

Race cars tend to endure harsher working conditions than do cars for daily street driving. For the most part (hopefully), most of us aren’t accelerating quickly, reaching hundreds of miles an hour, and requiring quick pit stops; these cars are put through their paces each time they’re taken out.

A great deal of engineering goes into the production of cars meant for the track. So much that engineering relationships go both ways; race car drivers have developed great expertise in all that goes into their cars, and close relationships with their technical teams, that have led to new business opportunities in manufacturing.

Most of what we hear about these relationships tends to go from manufacturing to track, though, and that’s where most of my personal knowledge of autosports has come from. Autosports are a Big Deal, and Stratasys SVP Pat Carey called F1 “the biggest sport in Europe, probably after soccer” (or “football” for everyone but Americans) when we chatted recently.

Stratasys had just announced a partnership with an autosports company. Sorry — make that another partnership with another autosports company. The 3D printing mainstay has established long-term relationships with the likes of McLaren, Penske, and now Andretti Autosports.

“There are different rules, different conditions in each racing sport,” Carey noted. “In each class, there’s a set of rules around each car: you can or can’t manipulate this or that feature for driver safety, driver comfort, performance, for cooling air flow. These are all things that can be variables, and there’s the concept of the unfair advantage. You win by either having a great driver or a competitive advantage.”

Many racing teams are hoping to have both. 3D printing is creating more competitive advantages, within the realms of fair play, by creating more optimized and driver-specific cars. Andretti, for example, is bringing a few 3D printers into play: the F370 for prototyping and the Fortus 450mc for carbon fiber tooling, jigs, fixtures, and end-use parts. This team races in the EU, the US, and Australia, and the work with Stratasys is, Carey noted, “a partnership exploring new uses.”

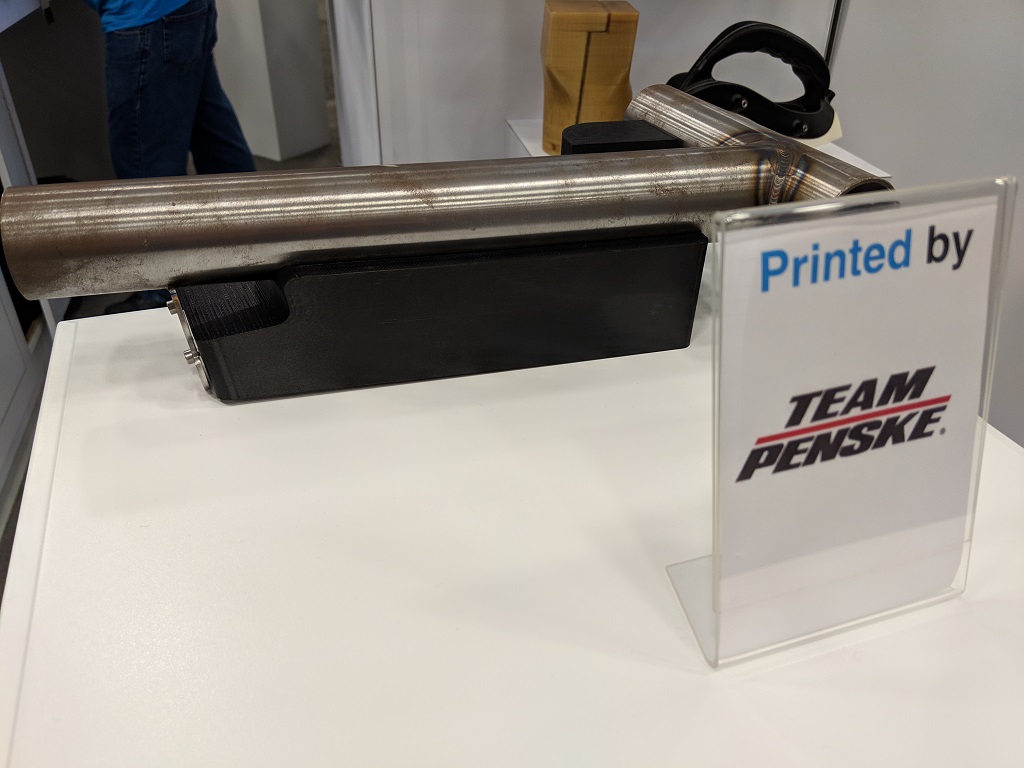

We looked at a couple of examples of specific parts that have proven useful on the racetrack for Penske, including a hollow carbon fiber tooling jig, which prints in 3-4 hours (above left), and a heavier jig to stand up to heftier parts (above right). Penske, which had the winning Indy car last year, has been seeing a lot of use from its 3D printers.

“Parts are all specific for racetracks, they’re all different. Some are flat, some are curved, some have different slopes and degrees of slope. Understanding these and preparing for specific conditions is important for winning races,” Carey noted.

All cars experience stresses in different ways, and what’s important when 3D printing is the creation “not of pretty parts, but of performance parts,” as Carey added.

Ultimately for Stratasys, at least, reasons for a growing focus on the busy racing world come down to two key factors:

-

It’s fun.

-

Racing pushes the cutting edge for automotive performance.

Via Stratasys

Charles Goulding and Preeti Sulibhavi consider how two prominent automotive firms, Ferrari and Ford, are using 3D printing.