One of the key applications for 3D scanning is automotive repair and enhancement.

There are quite a few powerful 3D scanners now available on the market, and many companies and individuals are scooping them up for a variety of uses.

But what are those uses? While hobbyists capture figurines and humans, and archaeologists capture ancient relics, by far the most common use is in the automotive industry.

There is a thriving market for maintaining classic automobiles by collectors, and also by those modding their current automobiles for enhanced performance. It turns out that 3D scanning technology is ideal for this application, and it’s becoming more widely used.

Thor 3D provided us with a recent case study showing the process of modding an automobile using 3D scanning, and it’s quite an involved process.

The study involved a project taking place at a Swiss engineering firm, Chromos Group for dAHLer, which produces modified BMW vehicles. Their project was to increase the aerodynamic efficiency of a BMW M240i and a BMW G80 by adding a splitter lip to the front bumper.

While the project obviously involves designing the new bumper attachment, there’s also a requirement for mating it with the existing bumper. That’s where 3D scanning comes in.

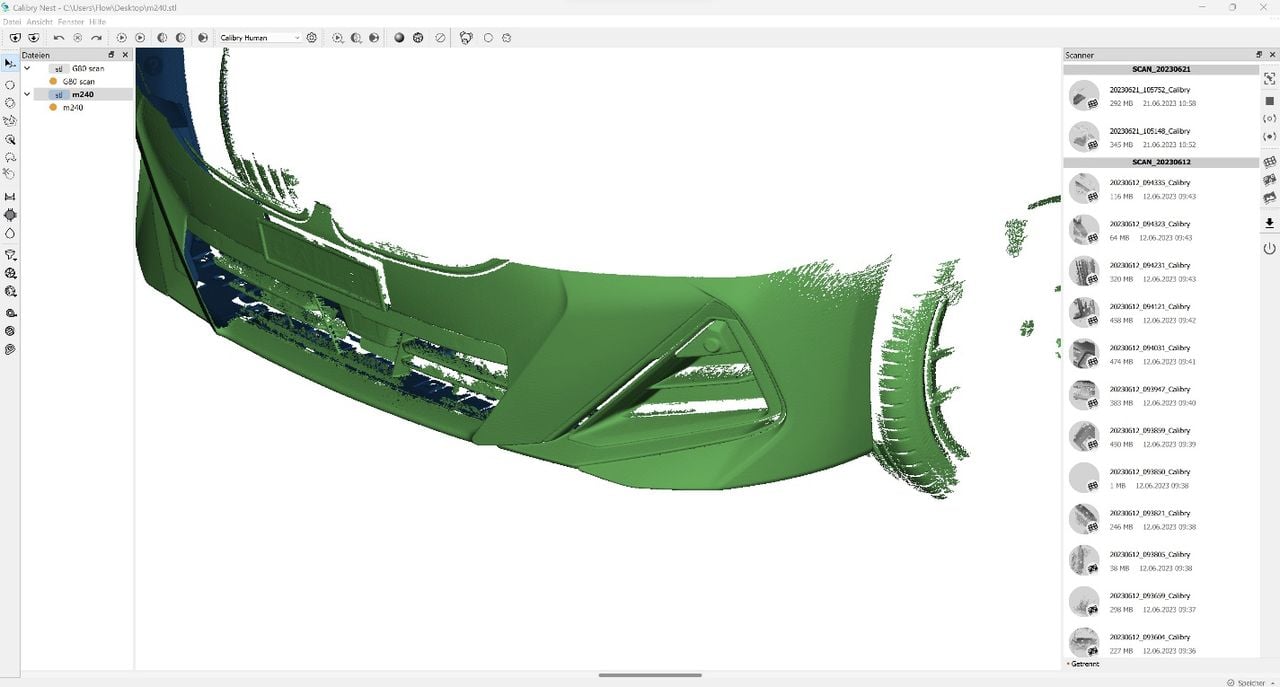

The techs used Thor 3D’s Calibry 3D scanner (which we reviewed previously) to capture the geometry of the existing bumper so that it could be used as the base in the attachment’s 3D model.

Typically this is done by “subtracting” the existing bumper geometry from the new attachment’s 3D model. This leaves a near-perfect interface between the two. Here there was likely other work done to include physical methods to more permanently attach the accessory.

Thor 3D reported that the scan operation took about 40 minutes to complete, and didn’t require the use of any tracking markers. Markers are often used by some 3D scanners to help maintaining tracking as the scanner is moved through 3D space. They are effective, but must be tediously applied to the subject — and then removed afterwards.

Another trick used in this project was to apply a special spray to the bumper prior to 3D scanning. This provided a non-reflective surface that makes it far easier to capture. Reflective surfaces tend to confuse 3D scanners, which are largely designed with the assumption that their emitted light is reflected back to the scanner.

A bumper is a large part, and therefore the techs had to capture it in several segments. These were knitted together afterwards using the Calibry Nest software that runs the scanner.

The techs used the scan to adjust the 3D models, as there were several different versions of the splitter lip. Each was 3D printed and then fitted to the automobile — which always fit perfectly due to the 3D scan.

Once the design was perfected, the splitter lip was then produced in lightweight carbon fiber material for end use.

It’s projects like these that leverage both 3D scanning, 3D printing and advanced software that properly demonstrate the capabilities of these technologies when used together.

Automotive applications are broad, and include several use cases beyond this particular scenario, including producing parts where the original is missing or damaged.

Via Thor 3D, Chromos Group and dAHLer