Researchers have discovered a straightforward treatment that could improve the ability to 3D print food.

3D Printed Food

3D printed food is a strange topic in the industry, as it is something that has been worked on for a very long time, but has yet to succeed in any notable way.

The only semi-successful ventures appear to be the few chocolate 3D printers, and most everything else is experimental in nature. Years ago 3D Systems announced a sugar 3D printer, the ChefJet, which was able to 3D print small sugary objects. However, the technology languished and was eventually transferred to Brill.

Most, if not all, food 3D printers use a cold extrusion process. Typically a fat syringe is attached to a piston containing some type of pasty material. Experiments have used ground meats, cheeses, peanut butter and similar substances. Some of them could be cooked after extrusion, but the process is interminably slow and results are not much better than a competent chef could make with their own hands.

One of the primary problems with food 3D printing is that food doesn’t happen to be a particularly viable structural material. In other words, as you build a food object taller, it tends to collapse as the material itself is not strong enough. That’s why most chocolate 3D printers seem to be making flat objects.

However, new research could point things in a different trajectory.

Improving 3D Printed Wheat Starch

Specifically, the researchers, from France and Brazil, were working on 3D printed wheat starch, as embodied in hydrogels.

They found this material to be 3D printable, but reproducibility was poor due to the lousy structural characteristics of the material.

However, when the wheat starch was pre-processed using a dry heating treatment (DHT), the properties of the material changed subtly. They say:

“DHT promoted slight molecular depolymerization, and reduction of starch crystallinity. Hydrogels ‘inks’ based on the modified starches showed lower peak apparent viscosity during pasting, higher structural strength at rest, higher resistance to external stresses, higher gel firmness, and lower syneresis than hydrogels based on native starch.”

And:

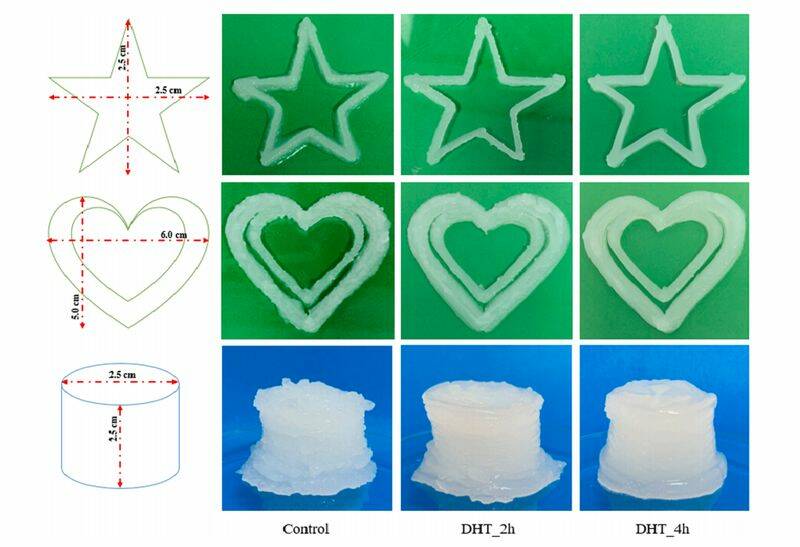

“The hydrogels based on starch DHT_4h showed the best printability (greater ability to make a 3D-object by layer-by-layer deposition and to support its structure once printed) and this ‘ink’ showed better reproducibility. Another point observed is that DHT extended the texture possibilities of printed samples based on wheat starch hydrogels. These results suggested that DHT is a relevant process to improve the properties of hydrogels based on wheat starch, making this ink suitable for 3D printing application.”

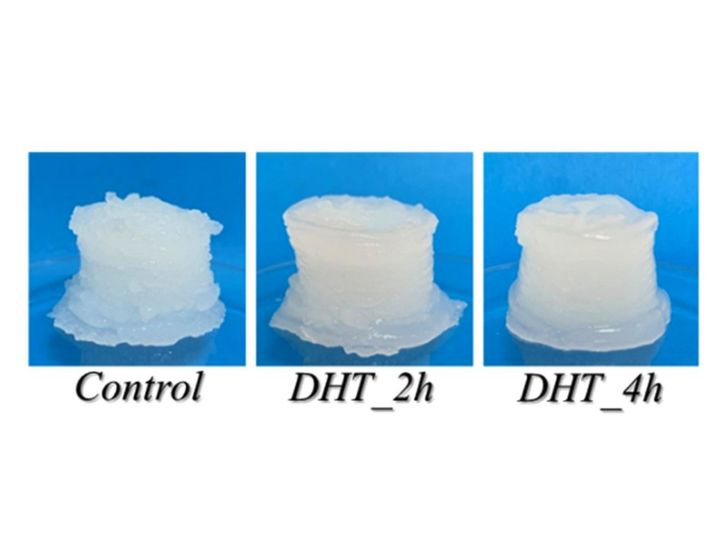

As seen in the images above, the DHT-treated 3D print samples provided better structural stability than standard wheat starch. The researchers also determined optimal DHT treatment styles during their experiments.

The outcome of this discovery is that it could be possible to produce a wheat-based 3D print material that could be used to 3D print more complex food geometries.

Whether that capability will drive a new market for food 3D printing is quite another matter. Even if one could reliably 3D print arbitrary food geometries in, say, wheat starch, would they be of sufficient value to justify the operation?

Food items tend to be relatively inexpensive as compared to other 3D printed objects. With a low carrying cost it’s highly unlikely even this development could trigger the food 3D printing market to greater heights.

Via Science Direct