Researchers have developed a unique way to decompose specific plastics: with embedded bacteria.

If you haven’t noticed, we are all in the midst of a microplastics crisis. Discarded plastic items gradually break down into smaller and smaller pieces, eventually becoming small enough that they begin moving around the planet through winds and waves.

Today virtually the entire planet is exposed to these particles, which are made from random chemicals. They may be the cause of future human and animal health problems, and we won’t know how bad it can get.

As a result of these concerns there are a number of initiatives to reduce the amount of plastic produced and discarded.

Recycling programs have been around for a while, but they are largely ineffective, particularly with the wide range of random plastics that might be encountered at a recycling depot. Plastics can only be effectively recycled if there is a consistent supply of identical material, and that just isn’t happening.

You’ve likely also heard of new regulations to, for example, ban plastic grocery bags, or single-use plastics like drinking straws. It’s also unclear whether these will achieve much, or even be accepted by the population.

A novel approach to the problem was undertaken by researchers. Their idea was to embed bacteria directly into the material itself. Then, when conditions are right, the bacteria would “eat” the plastic and prevent it from being blown around the environment.

But that’s a very hard thing to do: bacteria are living creatures that would clearly be destroyed when hot plastic is injection molded, for example.

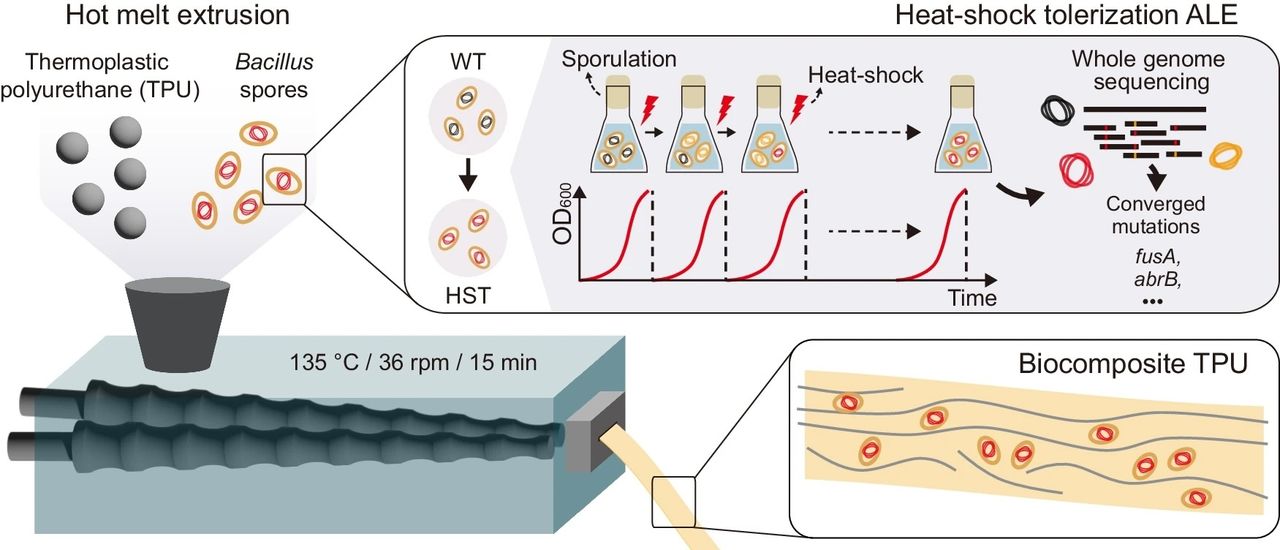

To overcome this issue, the researchers picked a particular combination of material and bacteria: flexible TPU and Bacillus subtilis. This particular bacteria was selected because it produces spores. These could be mixed in with the TPU for later activation.

However, the spores would be killed by manufacturing processes. Here the researchers bred a few generations of the bacteria, selecting those that survived increasing heat exposures. In the end they had a strain of the bacteria that was mostly able to withstand the 135C temperatures used during TPU manufacturing processes.

They produced a bicycle tire using the spore-laden material, and found that it actually had some interesting properties. It was somewhat stronger, as the spores somehow acted as rigid “bricks” in the microstructure. They also added some water-repellent properties.

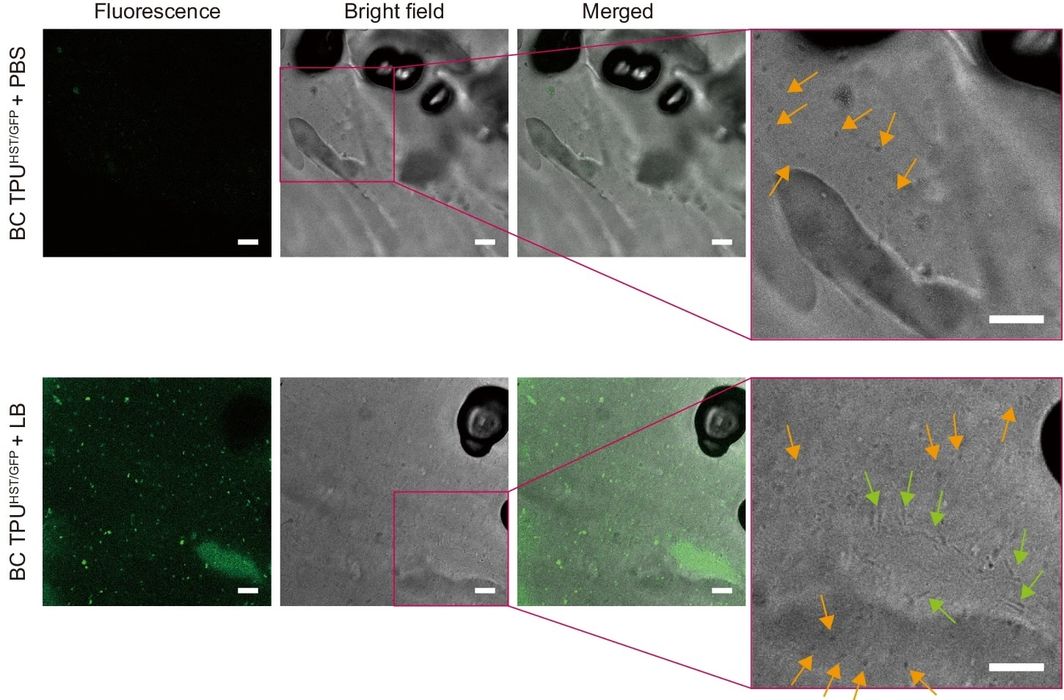

However, the big test was to see whether the bacteria would eat the TPU. To test this stage, the researchers placed the tire into a standard compost pile. After five months they found that 93% of the tire had been consumed, significantly more than would otherwise have been consumed.

While that proves the concept does work, there are a number of issues preventing this from becoming a common practice.

First, the system worked only because of the specific material and bacteria involved. For other materials other bacteria must be identified, if they exist at all. The bacteria must also produce spores that can be mixed with the material.

The material’s manufacturing temperatures must also be low enough to permit the survival of high-temperature spores.

My initial thought when reading about this research was whether it could be used in 3D printing. I could imagine a specialized filament that has the spores mixed in, which would automatically degrade when tossed in the compost.

However, after reading the paper it seems that this may not be the case.

Aside from the fact that only TPU has been tested at this point, the processing temperature during 3D printing will be quite a bit higher than 135C. TPU normally prints at 200C or more, which would surely exterminate the spores. For this to work in 3D printing even with TPU only, the spores would have to have vastly higher thermal resistance.

It was a good thought while it lasted.

Via Nature