I’m reading about a new and highly unusual 3D printing process, “HIAM”.

“HIAM” stands for “Hydrogel Infusion Additive Manufacturing”, and has been developed by researchers at CalTech in Pasadena, California. This is a printing process unlike any other.

The problem the researchers were trying to overcome were a number of challenges facing current metal 3D printing processes. Those existing processes are typically expensive, limited in resolution, require extensive post processing and need comprehensive air-controlled environments.

Some of those limitations and constraints are overcome with processes other than the most common process, LPBF, but almost always the resolution is poorer or there are other constraints.

HIAM Process

HIAM is quite different from any other process I’ve heard of. Instead of 3D printing the metal directly, a hydrogel scaffold is produced.

A hydrogel is a polymer of incredible lightness and transparency. They are often used in healthcare applications due to their exceptional biocompatibility.

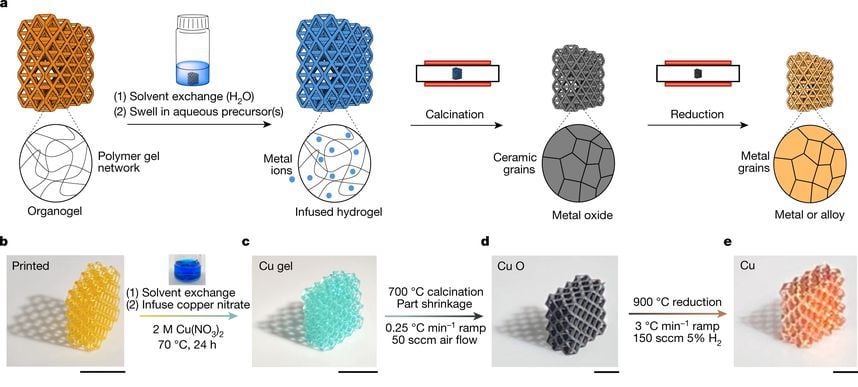

In HIAM, the hydrogel is not 3D printed directly. Instead, the researchers 3D printed architected organogels using a more-or-less standard DLP 3D printing setup. The resin is doped with photoinitators, making it susceptible to the DLP’s UV light.

Once printed they use a chemical solvent exchange to swap the N-dimethylformamide in the resin with water, transforming the 3D structure’s material to a true hydrogel.

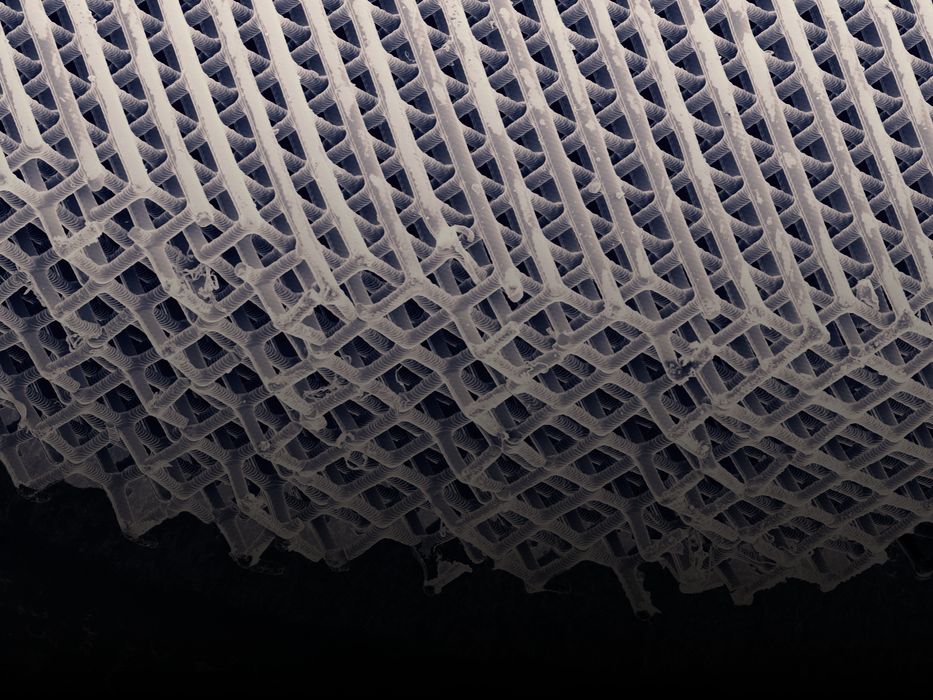

Then the interesting step takes place: these hydrogel structures are soaked in a metal salt precursor solution, which allows metal ions to deeply penetrate the hydrogel, which is an extremely porous material. Metal oxides form, which are then transforms into metal by high temperature gas application, with temperatures

During this step there is very significant shrinkage, up to 70% loss of dimension and a massive 90% in weight. However, knowing the target dimension for a part would simply require designing it proportionally larger for printing.

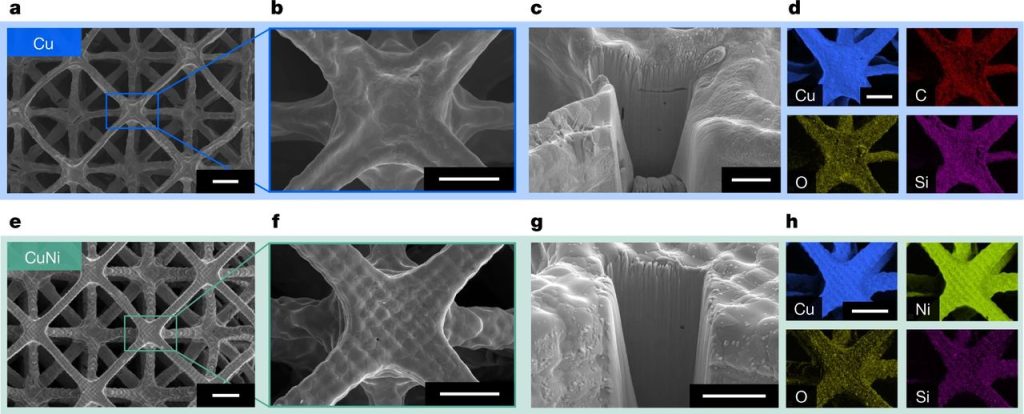

The research paper outlines their experiments using different metals, temperatures and conditions to explore the process.

The researchers examined the resulting metal structure and found it to be similar in hardness and microstructure to conventional methods of preparing metal part samples. This suggests the process could become a viable approach for commercial 3D printing of metal parts.

Along those lines, one of the members of the research team has founded a startup company, 3D Architech, to exploit the new technology. The company’s website describes the technology as:

“Revolutionizing Metal Manufacturing: Gel-based proprietary 3D printing technology enables previously unachieved designs and performance for metal additive manufacturing.”

3D Architech lists a number of benefits for their gel-based technology:

- SUPERIOR RESOLUTION: Super high-resolution net-shape metal manufacturing

- SUSTAINABLE 3D PRINTING: Easily recycle metal scraps to 3D-designed products

- LOW ENTRY COST: 10-100x lower cost for gel-based 3D printing equipment compared to state-of-art metal 3D printers

- VERSATILE MATERIAL SELECTION: Metals, ceramics, composites, and multi-materials

The low cost benefit is especially intriguing, as the HIAM process would not require lasers, which are the most expensive part of the more common LPBF process. In fact, the DLP technology used by the researchers is commonly available for less than US$1000.

I’m not certain how the metal scrap process works, but perhaps it’s possible to dissolve metals into a solution that could work with the HIAM process.

It should be very interesting to see how 3D Architech and several other unconventional new metal 3D printing processes collide with the existing older technologies.

Via Nature and 3D Architech (Hat tip to Benjamin)