![Close-up with Mr. Link in front of his costume pieces at LAIKA Studios [Image: Sarah Goehkre]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LAIKAsetvisitSGoehrke28529_img_5eb09ae2dc428.jpg)

LAIKA Studios opened its doors for a look into the making of Missing Link.

The film studio has long put 3D printing to use in creating memorable characters. Think Coraline, The Boxtrolls, ParaNorman, Kubo and the Two Strings. Each of these movies came to life with stunning stop-motion animation — and partially 3D printed characters.

Missing Link, LAIKA’s latest, is set for release on April 12. The movie features the most in-depth use of 3D printing to date, all using Stratasys’ advanced J750 system.

There are a few invitations I will never turn down. It turns out LAIKA is one of them, so at short notice it was off to Portland last week to see LAIKA’s HQ.

Heads of a few departments led the tour, with writer/director Chris Butler and producer Arianne Sutner kicking off the welcome with a brief private screening. Some 25 minutes of footage from the movie provided a glimpse into the odyssey ahead for audiences and the journey the LAIKA crew have undertaken over the last half-decade.

“This is definitely our most ambitious movie,” Butler said with a smile. “We always say that — and it’s always true.”

He described Missing Link as a travelogue “combining Indiana Jones, Sherlock Holmes, Around the World in 80 Days, and monsters: who doesn’t want that?” Missing Link represents an especially ambitious project with settings around the globe as well as the most expressive facial animation the studio has ever undertaken.

While the acclaimed Kubo and the Two Strings saw 64,000 unique faces made, more than 106,000 were 3D printed for Missing Link.

“We’re not proud because we made so many faces, but because we were able to put so many beautiful, superb, subtle details in them that brought these performances up a notch,” Sutner explained.

Costume designer Deborah Cook — who also helped shape the design for a soon-to-be-commercially-available shoe called Susan — walked through the creative process behind the remarkably elaborate period attire. Examining flora, embroidery, and textures specific to about 1890-1910, Cook and her team created bespoke designs (“nothing off-the-shelf”) to attire each unique character. Costuming is tricky enough, but doing so for 10” tall puppets who will need to be manipulated for close film capture represents its own unique set of challenges.

[A line-up of characters; Cook points to specific detailing / Images: Sarah Goehrke]

Techniques for the costumes included laser cutting, stitching, embossing, craft foam, hand-dyed fabrics, handmade macramé, and much more. I was especially intrigued by the particular weighting systems developed to allow each cuff and collar to lay exactly where animators would need them in a given scene for frame-to-frame consistency.

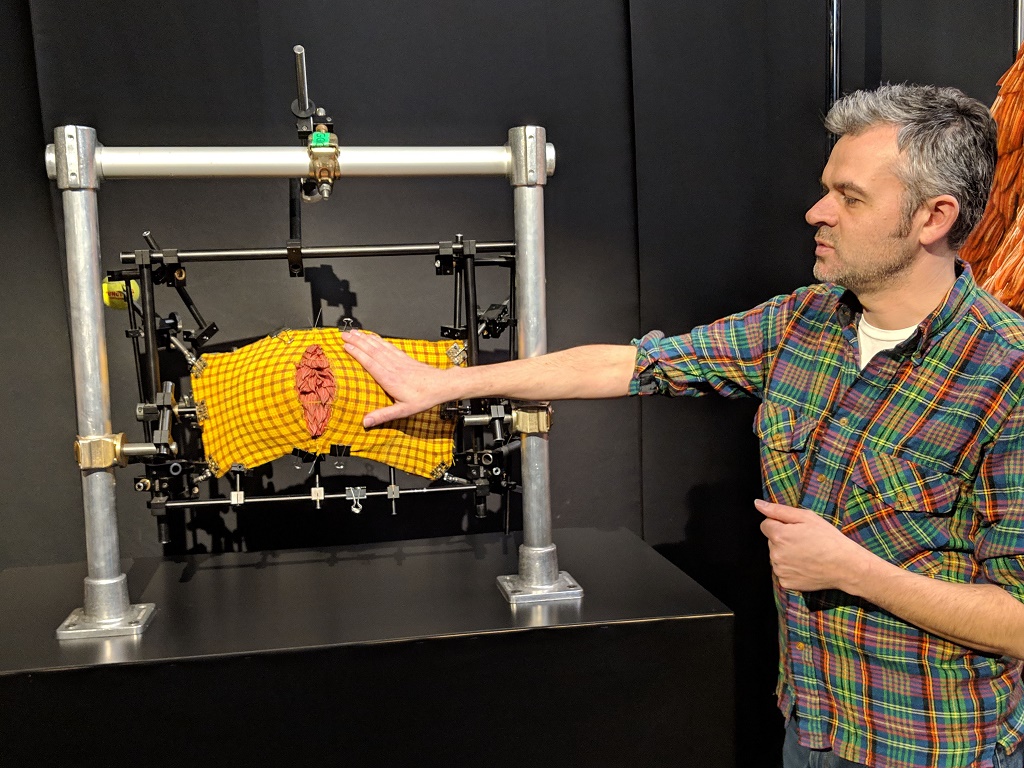

Creative lead John Craney then walked through the needs of those puppeteers. If, he said, one could talk about what would make a stop-motion puppet the most challenging design, it would be a husky, large, robust character over a foot tall and covered in hair (this last the biggest challenge for a puppet). And “Mr. Link ticks all these,” he concluded. So for this production, Mr. Link was the most sophisticated puppet created, with involved internal operations and a great deal of thought put into how to make this furry creature without fur. He’s made of silicone that can hold the same look frame to frame and allow for maximum control.

![A complex puppet [Image: Sarah Goehkre]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LAIKAsetvisitSGoehrke282429_img_5eb09ae4452f1.jpg)

While Mr. Link was the most sophisticated, he was in great company: 107 characters had puppets made, supplemented by more in the background created with CG. Any characters coming into “critical contact” with the main characters (that is, touching or crossing paths with) required physical representation. Each of these characters required a unique look — the travelogue takes the primary trio of characters from the Americas to Europe to Nepal to other fanciful locales each with distinct locals — and a puppet hospital ensured that they stayed in good repair.

Brian McLean, LAIKA’s Director of Rapid Prototyping, then shared what was for me the main attraction of the visit: the 3D printing of the faces. We’ll go into more detail in the second part of this feature.

3D printing for stop-motion films takes its cues from replacement animation techniques that had been developed for earlier films. As a base of comparison, McLean pointed to Nightmare Before Christmas, as Jack Skellington’s expressions were sculpted and sculpted again with slightly different emphases. Working on Coraline, the thought advanced: “We thought to take this and fuse it with 21st century technology,” McLean said, gesturing at a few 3D printers displayed to demonstrate LAIKA’s history with the tech.

[3D printed faces; McLean discusses their creation / Images: Sarah Goehrke]

For Coraline, animators created 20,000 faces, made on an Objet Eden260. Each came out white and was hand-painted, including separate denture pieces made for the mouths.

“This tech was amazing,” McLean said of the studio’s initial foray with 3D printing. “It set us off on this journey of 3D printing.”

For ParaNorman, the studio worked with a ZPrinter 650, which at the time was the only available color-capable 3D printer. A Connex3 was missing from the lineup, but was LAIKA’s “introduction to resin color printing” and saw use for three characters in Kubo. LAIKA became a beta user for Stratasys’ J750 before that machine’s official launch in 2016 and then acquired “the first five off the assembly line when they were released.”

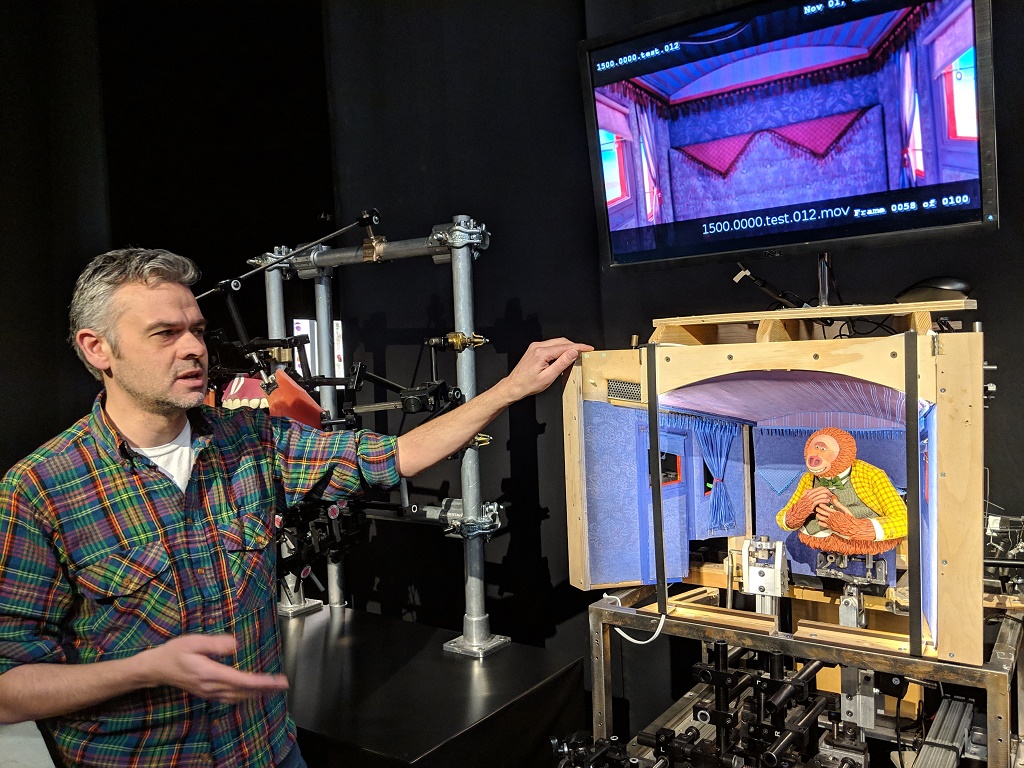

Moving on to the movements of the characters, head of rigging Ollie Jones noted that “everything that moves needs a rig.” This aspect of animation was pretty new to me; once the characters are made, they need to be captured on film, looking as though they’re moving organically. The rigs made straddled the line between remarkable feats of engineering and impressive feats of binder clip, which is a good place to be.

Syringes to blow air, “jet packs” to allow animators to move puppets without touching and disrupting costumes, scaled-up versions of Mr. Link’s rear (“this was the first and maybe last time we’ll create a butt at 300% scale”) and mouth (at 600% scale, with 3D printed teeth and cheeks cast from a 3D printed design — and with “the most axes [of movement] we’ve put on a tongue before”): these rigs are really movie magic at its finest.

[Jones points to a 300% bum and the rigging for a moving carriage; help, I’m trapped in a 600% scale Bigfoot mouth / Images: Sarah Goehrke]

Production designer Nelson Lowry then led a thoughtful tour through the look and feel of the film. If you see Missing Link (and after this on-site, I highly recommend that you do), pay close attention to the color scheme. Once the action sets off around the world, there is no black, white, or grey to be seen: “It exposes people to the world.” The movie goes through 60 distinct locations.

[Inside the black-and-white club; outside the Yeti temple as seen through a scaled-up version of the ice bridge that leads to it / Images: Sarah Goehrke]

While most set pieces were handmade, demonstrating incredible artistry and attention to detail, about 5% of them were 3D printed.

“The thing is, someone still has to design it on a computer; it doesn’t really save that much,” Lowry explained of the still relatively minimal use of 3D printing.

This also provides an interesting thought on barriers to adoption we’ll dive into more later.

[Looks into Lionel’s study and a Western town with Lowry / Images: Sarah Goehrke]

Rounding out the tour was a look at the way the film itself is rounded out: visual effects. VFX supervisor Steve Emerson has been with LAIKA for 11 years, contributing to all five of the studio’s films to date.

“There was a turn at ParaNorman toward hybrid techniques to tell the stories we wanted to tell, to leverage tech to do that, and to use that tech respectfully to stop-motion animation,” Emerson began. “VFX doesn’t generate in a vacuum; it’s really a collaborative effort.”

The VFX process runs parallel to other production aspects, he continued, noting that “as they’re making puppets, we’re right there with them.” Primarily using MAYA software, the VFX team also uses MARI, KATANA, NUKE, Silhouette SFX, OCULA, and FURNACE for various digital functions.

Missing Link with its ambitious scope included “the largest shot count” for LAIKA to date. The 1486 shotes, which Emerson ‘likes to think of aas 1486 little stories,’ required 112 million processor hours (or about 12,785 years), 400 hosts, and a 10G network. Continuing by the numbers, 182 digital puppets also involved 531 digital assets. More than 1,000 rigs were digitally removed from shots, and other cleanup work involved those intricate 3D printed faces. Because each face fits around a base of character eyes, the line where the expressive face plate connects to the puppet base had to be digitally removed — for all 106,000 faces.

“We’re trying to get audiences to empathize with ten-inch-tall puppets moved around by human hands. They’re the stars; we’re helping tell their stories,” Emerson said.

![Storytelling is key for LAIKA and for the VFX team, Emerson notes [Image: Sarah Goehrke]](https://fabbaloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LAIKAsetvisitSGoehrke2818329_img_5eb09ae935559.jpg)

Going backstage at Missing Link was a day I won’t soon forget. The expansive space at LAIKA Studios was broken up into dozens of areas for filming, with puppet-sized sets ready to tell a larger-than-life adventure tale.

For specifically on the 3D printing work put into the film’s faces, check out part two.

Via LAIKA